|

| December 26, 2018 | Volume 14 Issue 48 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

50 Years Ago: Apollo 8 first human flight to moon

At Christmastime a half-century ago, millions around the world paused to follow the flight of Apollo 8. For the first time, humans left Earth for a distant destination -- the Moon. The mission was a key step toward meeting President John F. Kennedy's goal of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to Earth" by the end of the decade.

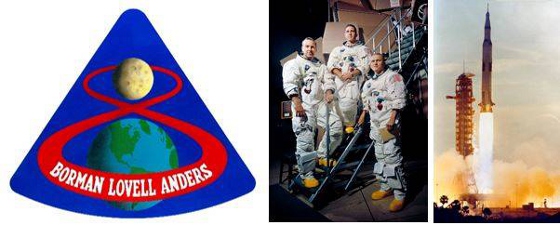

In the early morning of Dec. 21, 1968, at Kennedy Space Center's (KSC) Launch Pad 39A, the five engines of the Saturn V's first stage came to life precisely on time at 7:51 AM EST, powering up to their full 7.5 million lb of thrust. The brilliance of the flame was like a second sunrise. At the top of the 6.5-million-lb rocket, Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, James A. Lovell, and William A. Anders were strapped inside their Command Module (CM), the first humans to experience a Saturn V launch.

After 2.5 minutes, the first stage had exhausted its fuel, burning it at the rate of 13 tons every second, and had carried the vehicle to an altitude of 40 miles. The second stage took over, burning for more than 6 minutes before it too fell away. The third stage, called the S-IVB, finished placing Apollo 8 into Earth orbit 11.5 minutes after liftoff.

Left: Apollo 8 mission patch. Middle: Official photo of the Apollo 8 crew, (left to right) James Lovell, William Anders, and Frank Borman. Right: Liftoff of Apollo 8.

As soon as the rocket had cleared the launch tower, control of the mission transferred from the Launch Control Center at Launch Complex 39 to Mission Control at the Manned Spacecraft Center, now the Johnson Space Center in Houston. Three teams of controllers, led by Lead Flight Director Clifford E. Charlesworth and Flight Directors Glynn S. Lunney and Milton L. Windler, working in eight-hour shifts, monitored all aspects of the mission until splashdown.

The capsule communicator (or Capcom), the astronaut in Mission Control who spoke directly to the crew during the launch, was Michael Collins, who at one time was part of the Apollo 8 crew but was sidelined with a bone spur in his neck and replaced by Lovell less than five months before the flight. Other Capcoms during the mission were Thomas K. Mattingly and Gerald P. Carr.

Left: Lead Flight Director Charlesworth monitoring his console during the launch of Apollo 8. Right: A view of the S-IVB third stage shortly after TLI and spacecraft separation; the ring-like structure at the left is the LTA-B.

Once in orbit, the crew spent the next two and a half hours checking out its spacecraft, still attached to the S-IVB third stage, ensuring all was ready for the next phase of the mission. Then came the call from Mission Control that had never been uttered before during a space flight: "Apollo 8, you are Go for TLI." With those words, meaning Trans Lunar Injection, Capcom Collins committed the mission to break the bonds of Earth's gravity and set a course for the Moon.

Near the end of the second revolution around the Earth, the S-IVB's engine fired for a second time. This burn lasted more than 5 minutes and increased Apollo 8's speed from about 17,400 mph to 24,226 mph, enough to overcome Earth's gravity and send it on a trajectory toward the Moon. Soon after the burn ended, the astronauts separated their spacecraft from the spent S-IVB and used the Service Module (SM) Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters to maneuver a short distance away and turn around to inspect and photograph the third stage.

On future missions, crews performed a transposition and docking maneuver to remove the Lunar Module (LM) from the S-IVB. But on Apollo 8, the third stage only carried a LM Test Article-B (LTA-B), used to partially simulate the mass of a LM during launch and which remained attached to the stage. A separation burn moved the spacecraft away from the S-IVB, which vented its remaining fuel to send it into solar orbit.

Series of views of the receding Earth taken by Apollo 8 astronauts during the translunar coast, including the first ever taken of the whole Earth in a single frame (third from left).

The astronauts now had some time to look out their windows and could visibly see the Earth receding as they sped away from their home planet. They quickly passed the previous human spaceflight altitude record of 850 miles set by Charles "Pete" Conrad and Richard F. Gordon during the Gemini 11 mission in 1966. At the same time, with the Earth's gravity still exerting influence on the spacecraft, their velocity was gradually decreasing. The Apollo 8 astronauts became the first humans to traverse the Van Allen radiation belts, a region of charged particles trapped by the Earth's magnetic field first discovered by NASA's Explorer 1 spacecraft in 1958.

As their next task, the astronauts deployed the spacecraft's high gain antenna at the base of the SM to maintain good communication with Mission Control at lunar distances. They also put the spacecraft into Passive Thermal Control mode, often referred as "barbecue mode," in which it slowly spun on its longitudinal axis to evenly distribute the extreme temperatures encountered in space. The spacecraft completed one rotation on its axis every hour. With these major activities behind them, the astronauts finally changed from the spacesuits in which they launched to more comfortable overalls, which they wore the remainder of the flight. They also ate their first meal of the flight, about nine hours after liftoff.

About two hours later, the crew executed the mission's first midcourse correction maneuver, using the SM's Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine to refine their trajectory. This engine, thoroughly tested during Apollo 7 in Earth orbit, was critical for getting the spacecraft into and out of lunar orbit. For this maneuver, the SPS engine fired for 2.4 seconds and slightly increased the vehicle's speed. This maneuver was so accurate that two additional planned burns before they reached the Moon's vicinity were not required. Borman then began his first sleep period -- for this mission, as with Apollo 7, at least one crewmember remained awake at all times. On later Apollo flights, this practice was abandoned as unworkable. Lovell and Anders began their sleep once Borman was awake again, after a short five-hour sleep period.

For the next two days, the Apollo 8 astronauts continued their coast to the Moon, a relatively uneventful time marked by periodic navigation checks and spacecraft housekeeping chores. As part of the Public Affairs Office effort to keep the crewmembers up to date on current events, Capcom Collins informed them that the crew of the USS Pueblo, held by North Korea for 11 months, was freed on Dec. 23. Borman replied, "Wonderful!"

At around 31 hours into the mission, the Apollo 8 astronauts began their first TV broadcast when they were nearly 140,000 miles from Earth. They transmitted black and white images of their activities inside the cabin, including Lovell preparing a meal, but attempts to show the home audience views of the Earth through the windows during this broadcast were not successful. This first transmission lasted 23 minutes.

A second transmission at 55 hours was more successful, as the crew learned to tape the proper filters to the camera's telephoto lens, showing TV viewers at home a view of Earth from more than 200,000 miles away. Since the TV image was in black and white, Lovell provided a verbal description of the colors as the crew saw them.

In describing the apparent size of the Earth, Lovell said, "It's about as big as the end of my thumb" held at arm's length.

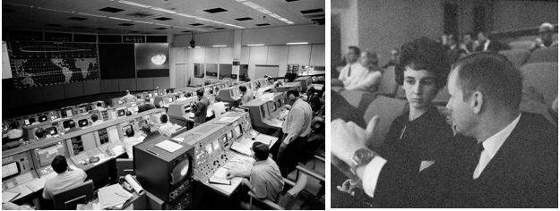

Minutes after the end of the second broadcast, which lasted about 26 minutes, Apollo 8 and its crew entered the Moon's sphere of influence, or more accurately where the Moon's gravitational influence became the dominant force acting on the spacecraft. They were about 200,000 miles from Earth and 35,000 miles from the Moon and had slowed down to 2,225 mph. Their speed started increasing as the Moon started pulling them toward it. Two of the astronauts' wives, Marylin Lovell and Valerie Anders, visited the Mission Control viewing room during this time.

A second midcourse correction at 61 hours using the RCS thrusters lasted about 12 seconds to slow the spacecraft slightly to lower the closest approach to the Moon's surface.

Left: View of Mission Control during the second TV broadcast on Dec. 23, with the Earth displayed on the large wall screen. Right: Valerie Anders (middle), wife of Apollo 8 astronaut Anders, visits the Mission Control gallery, with backup Apollo 8 Commander Neil Armstrong (right).

At 68 hours 58 minutes into the flight -- precisely on time on Dec. 24, 1968 -- Mission Control lost contact with Apollo 8 and its crew. And everyone at NASA and onboard Apollo 8 was happy about that.

It meant that the spacecraft and crew were on a precise trajectory to swing behind the Moon, and if all went well, to fire the Service Module's Service Propulsion System (SPS) engine to slow their velocity just enough to allow the Moon's gravitational field to capture them. With a successful Lunar Orbit Insertion (LOI) burn, they would become the first crewed spacecraft in lunar orbit, and Mission Control would regain the signal after 32 minutes and 37 seconds. If it didn't fire at all, they would regain the signal in 22 minutes and it meant Apollo 8 was heading back to Earth. And of course, a variety of engine malfunctions could result in different signal reacquisition times.

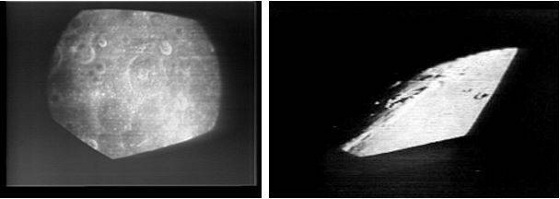

While NASA and the world waited to hear from Apollo 8, Borman, Lovell, and Anders busied themselves with preparing for the engine burn. Just a few minutes before ignition, the crew got its first glimpse of the Moon. During the 66-hour coast to the Moon, the spacecraft was oriented with the SPS engine facing in the direction of travel, so the windows were pointed toward the Earth. Now, about 70 miles above its surface, the Moon finally entered into their field of view and the Apollo 8 crewmembers became the first humans to directly see the far side. Exactly on schedule, the SPS engine lit up and burned for just over 4 minutes, placing Apollo 8 into an elliptical 70-by-195-mile orbit around the Moon.

Just as expected, Mission Control began receiving telemetry from Apollo 8 as it came out from behind the Moon, followed by Lovell's simple call, "Houston, Apollo 8. Burn complete." From Mission Control, Capcom Carr replied, "Apollo 8, this is Houston. Good to hear your voice."

As they passed over the Sea of Fertility, Lovell provided this commentary: "The Moon is essentially grey, no color; looks like plaster of Paris or sort of a grayish beach sand. We can see quite a bit of detail. The craters are all rounded off. There's quite a few of them, some of them are newer." They also flew over the two most easterly of the five potential sites for the first Moon landing, providing verbal narration and taking photographs.

For the next 20 hours, Apollo 8 remained in orbit around the Moon, each revolution taking about two hours, of which 45 minutes was spent out of radio contact with Earth while the spacecraft flew behind the Moon.

The astronauts began their second revolution with a 12-minute TV broadcast showing the Moon as it appeared to them through the spacecraft window. At the end of the second revolution, once again behind the Moon, the crew preformed the second LOI burn using the SPS engine and lasting less than 10 seconds to circularize the orbit at 70 miles. The trio conducted extensive photography of the lunar surface, mostly of the far side given it had more sunlight, but also of proposed landing sites on the near side. At the beginning of the fourth revolution, as they were about to round the back of the Moon, the astronauts caught sight of the Earth appearing above the lunar limb.

"Oh, my god, look at that picture over there," Anders said. "Here's the Earth coming up. Wow, is that pretty."

Anders snapped some of the most iconic photos of the Apollo program, first in black and white and then the more famous color Earthrise images.

One of the most famous photographs of the Apollo era, the Earth appearing to rise above the Moon's limb, taken by the Apollo 8 crew on Dec. 24, 1968.

Borman, Lovell, and Anders began their ninth revolution with a TV broadcast, first showing viewers the Earth and then pointing the camera down to the Moon's surface. As the spacecraft flew on, they described the terrain they were seeing, including the possible landing site for the first lunar landing in the Sea of Tranquility. Each crewmember provided the viewers with his personal impression of the Moon and the mission. They closed out the 27-minute broadcast by taking turns reading the first 10 verses from the Book of Genesis, and then signing off by wishing everyone on Earth a Merry Christmas. It is estimated that 1 billion people in 64 countries around the world were tuned in to the Christmas Eve broadcast.

Left: Still image from the first TV transmission from lunar orbit. Right: Still image from the second TV broadcast from lunar orbit, which concluded with the reading from the Book of Genesis.

At the end of their 10th revolution, at 89 hours and 19 minutes into the flight and once again out of communication with Earth, the Apollo 8 astronauts fired the spacecraft's SPS engine for the Trans Earth Injection burn. While Mission Control waited for confirmation of the burn, the crew had its last look at the Moon's far side. Then, precisely on schedule, contact was re-established indicating a successful 3-minute and 23-second burn.

Apollo 8 was heading home to Earth.

Lovell radioed to Houston, "Please be informed there is a Santa Claus." It was now Christmas Day in Houston.

Source: NASA (Editor, Kelli Mars)

Published December 2018

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy